CHELCY WALKER

In Einsohn’s chapter on “Spelling and Hyphenation” from The Copyeditor’s Handbook, she first encourages copyeditors to improve their spelling by “star[ing] at lists of hard words.”[1] Whether she means this as a comical commentary or not, her recommendation does seem to touch on two unfortunate aspects of English spelling: there are indeed “hard words,” and sometimes all you can do is stare at them in order to remember them. No amount of mnemonic devices can help you remember that “idiosyncrasy” is spelled with an ending “s” instead of a “c” while “aristocracy,” “democracy,” and “bureaucracy” each end in the suffix “-cracy.” Even an extensive study of etymology may still leave you puzzling over the blatant anti-phonetic spelling of “colonel” and “corps.” But at least these words have a right-or-wrong answer. Equal variants, much to the copyeditor’s dismay, can be spelled in more than one way. Regarding these, Einsohn offers two guiding principles: follow your style guide and ensure consistency. However, should the burden ever be laid upon a copyeditor to develop their own style guide, are there resources that can help copyeditors make the “right” choices between equally “right” spellings? Dictionaries offer little help, since many of them affirm several spellings of a word as equally correct. However, I would argue that dictionaries ought to help settle more of these debates by reflecting common speech and writing practices and in turn abandoning out-of-date spellings that only further confuse the already-mystifying nature of American English spelling.

After all, early dictionary writers had no qualms about guiding American spelling in its early stages of orthography. Noah Webster, in his Compendious Dictionary of the English Language (1806), sought to find common ground between the conservative British spellings and the more radical revisions of a few of his contemporaries. He adopted some of the current practices of his day by eliminating several double consonants and double vowels and aiming for brevity when possible.[2] In doing so, Webster solidified many of the American standard spellings we recognize today, and his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) established itself as authoritative, primarily because of his “ability to select spellings that American printers already favored….”[3] In the absence of a national “academy” for American English, dictionaries have been the primary influence in spelling reforms to date. The precedent set by Webster commissioned dictionaries to strive for a careful balance of descriptivism and standardization in order to remain cogent. While I value the descriptive nature of the dictionary, if it is to remain inherently democratic, it must continue to listen to the voices of the people and adjust itself accordingly.

This is perhaps why several of the equal variants listed by Einsohn became so troubling to me. As I perused the list, I noted that a majority of the variants had asterisks, indicating that “many book publishers have unshakable preferences among these pairs.”[4] If these “industrywide preferences” do exist, then what is it that keeps a word on the equal variant list rather than moving toward the preferred/secondary variant list that Einsohn describes later?[5] And further, why have a preferred/secondary variant list at all unless these variants are reinforced by the industry and common writing practices? In an effort to explore a method for fellow copyeditors to select a preferred equal variant and to illuminate the discrepancies between dictionaries and industry preferences, I chose three variants from Einsohn’s list and consulted both Google Ngram and three dictionaries: the Oxford English Dictionary, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, and the default dictionary for Google, Dictionary.com. For my searches in Google Ngram, I searched within the “English” corpus. Google Ngram does allow you to select other corpuses, such as “British English,” “American English,” or “English fiction,” however my primary interest was to determine the widest usage of the term, and thus I set “English” as my search criteria.[6]

The first variant paring I chose was “Shakespearean” versus “Shakespearian.” Having never seen the latter in print, I was surprised by the OED’s preference. When searching for “Shakespearean” in the search engine, you are automatically re-routed to the entry for “Shakespearian,” and a note follows which indicates that the variant spelling “Shakespearean” is acceptable.[7] The opposite is true for Dictionary.com: “Shakespearian” is routed to “Shakespearean” with a similar note.[8] The M-W Collegiate shows four spellings in the same entry that are all acceptable: “Shakespearean or Shakespearian also Shaksperean or Shaksperian.”[9]According to Google Ngram, a preference for “Shakespearean” was established at the beginning of the twentieth century, and the divide between these two has grown since then.

Figure 1. Spellings of “Shakespearean” versus “Shakesperian,” 1800–2000.

As you can see in Figure 1, “Shakespearian” continues to taper toward the end of the century.

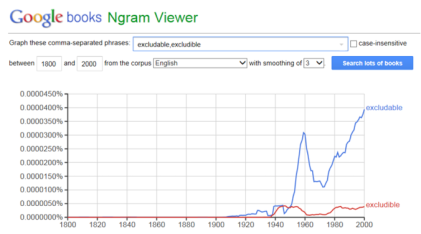

The next variant pairing I chose was “excludable” versus “excludible.” According to M-W Collegiate, either spelling is acceptable, and both are included in the same entry.[10] Dictionary.com routes the search “excludible” to the entry “excludable,” with a note that the “-ible” suffix is acceptable.[11] Most interesting is the OED’s treatment of the word; “excludible” is not even listed.[12] The suggested entry is “excludable,” and no reference to a variant is given. According to the Google Ngram graph in Figure 2, this strong preference for “excludable” is also apparent.

Figure 2. Spellings of “excludable” versus “excludible,” 1800–2000.

This seems logical, in part because the term “excludability” is only spelled as such and does not have a variant spelling of “excludibility.” It makes one wonder why other dictionaries continue to offer the “-ible” variant as an equally acceptable option, when the industry has largely rejected it and the OED does not acknowledge it.

Lastly, I chose a primary/secondary variant, because I think the discrepancies here are just as apparent and distressing as the equal variants. Regarding the two terms “cancellation” versus “cancelation,” the M-W Collegiate treats them as equals, and both the OED and Dictionary.com re-direct you to the “cancellation” entry.[13] But here, Dictionary.com references the alternative acceptable spelling, but the OED does not. Google Ngram also shows an overwhelming preference for “cancellation” in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Spellings of “cancellation” versus “cancelation,” 1800–2000.

Because of the widespread preference for one of the two variants in each example, there is little chance that the less-predominate spelling will ever overtake the more-predominate spelling. As Einsohn points out, these industry-preferred spellings will continue to reinforce themselves: “The lexicographers’ decision to label a spelling as a secondary variant is based on the prevalence of that spelling in publications from which evidence of usage is culled. But once a spelling is labeled as a secondary variant, it is less likely to appear in print.”[14]And similarly for equal variants, the more publishers that adopt a similar preferred variant, the more likely this variant will continue to be accepted and used.

While I admire these dictionaries’ historical regard for variant spellings, at a certain point they need to retire these outdated spellings in order to reflect the choices of the industry, the publisher, the copyeditor, and the common writer. English spelling is confusing enough. Perhaps it is time for these dictionaries to stop waiving the banner of equality for these variants and pick a side. Clearly the masses have already done so.

NOTES

[1] Amy Einsohn, The Copyeditor’s Handbook, 123.

[2] Richard L. Venezky, “Spelling,” 345.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Einsohn, 125.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For each of my three variant searches within Google Ngram, the British English, American English, and English fiction corpuses all show a similar disparity of usage. The most notable departure was the consistent usage of both “Shakespearean” and “Shakespearian” between 1940 and 1960 within the British English corpus, whereas the spelling “Shakespearean” in American English had already taken precedence by this time.

[7] OED Online, s.v. “Shakespearian, adj. and n,” accessed March 5, 2015, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/177324?redirectedFrom=shakespearean.

[8] Dictionary.com, s.v. “Shakespearean,” accessed March 4, 2015, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/shakespearean.

[9] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate(R) Dictionary, s.v. “Shakespearean or Shakespearian Also Shaksperean or Shaksperian 1,” accessed March 4, 2015, http://ezproxy.stthomas.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com.ezproxy.stthomas.edu%2Fcontent%2Fentry%2Fmwcollegiate%2Fshakespearean_or_shakespearian_also_shaksperean_or_shaksperian_1%2F0.

[10] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate(R) Dictionary, s.v. “Excludable or Excludible,” accessed March 4, 2015, http://ezproxy.stthomas.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com.ezproxy.stthomas.edu%2Fcontent%2Fentry%2Fmwcollegiate%2Fexcludable_or_excludible%2F0.

[11] Dictionary.com, s.v. “excludable,” accessed March 4, 2015, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/excludable.

[12] OED Online, s.v. “excludable, adj.,” accessed March 05, 2015, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/240919?rskey=QgjXt1&result=1

[13] Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate(R) Dictionary, s.v. “Cancellation Also Cancelation,” accessed March 5, 2015, http://ezproxy.stthomas.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com.ezproxy.stthomas.edu%2Fcontent%2Fentry%2Fmwcollegiate%2Fcancellation_also_cancelation%2F0; OED Online, s.v. “cancellation, n.,” accessed March 5, 2015, http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/26926?redirectedFrom=cancellation; Dictionary.com “cancellation.,” accessed March 5, 2015, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/cancellation.

[14] Einsohn, 126.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Einsohn, Amy. The Copyeditor’s Handbook: A Guide for Book Publishing and Corporate Communications Third Edition (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2011), 123.

Venezky, Richard L. “Spelling” in The Cambridge History of the English Language. Ed. John Algeo. 1st ed. Vol. 6. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.), 345. Cambridge Histories Online. http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy.stthomas.edu/10.1017/CHOL9780521264792.011 (accessed March 3, 2015).

One thing to consider with dictionaries getting rid of out-of-date spellings is the fact that we may be getting rid of part of our textual history. Would there be a separate collection of all of these variations, or would they just be left to the wayside to be forgotten? I’m sure there have been many cases of this through the development of the English language and simply the lack of documents to show a lost variant spelling, but with our technology and ability to catalog today, I think the question is not should we abolish these confusing spellings but how we should abolish them.

I agree with the point you make about the preferences in variation being the voice of the masses. If there is a general consensus on which variation should be retained, then it does not seem difficult to save these variations in another sort of “dictionary for variant spellings.” However, there is always the potential for there to be disagreements and confusion, leaving us with pulling out old spellings and deciding we should use those now. The future I am envisioning for the English language using this method seems to be one like fashion, where words are trendy, fall out of fashion, then come back. This seems to make a case for leaving these words out altogether to be forgotten. But I still can’t help but worry over the value in seeing variant spellings and being able to pinpoint a cultural time in history via language. I may never find an answer to this conundrum, but your post has posed some interesting thoughts to ponder!

LikeLike

Chelcy, thanks for a great post on the issue of equal variants in spelling. Because we just edited two articles for class, I really feel that exploring and discussing this issue of choosing between multiple spellings came at an opportune time. While I agree with Angie that in eliminating the equal variants from dictionaries we might lose a piece of textual history, I think we also have to consider the needs of users today – not only editors, but readers as well. For editors, are there too many demands to be constantly looking up how to spell “cancellation” or “cancelation” for different texts and constantly having to remember to switch between “American English” or “British English” or “English fiction?” (I’d really love to know the reasoning behind “fiction” getting its own subcategory in the English corpus, by the way. How can writing in “fiction” possibly be so much different that it needs its own set of spellings?) And for readers, how confusing to see both “Shakesperian” and “Shakesperean” and wonder which is correct and which should they use in their own writing in the future? At some point, doesn’t it behoove us to simplify, and pick a preferential spelling? After all, we have had no trouble doing so in the past. As Williams and Bizup write in their text Style, “When a language has different regional dialects, that of the most powerful speakers usually becomes the most prestigious and the basis for a nation’s ‘correct’ writing.” (10)

It seems to me that the question of giving equality to the variant or of eliminating it entirely, is very reminiscent of the issue that Grace brings up in her post regarding the job of the textual editor in deciding “which histories are important to include [in a text] and which histories might be excessive.” Perhaps we can apply this logic in deciding to choose certain spellings as more important, and leave off some of the variants, which may be excessive.

LikeLike

I agree with that we would be losing some textual history if we abolish outdated spellings, although that’s probably not anybody’s goal. I guess I don’t really mind standardizing spelling, but I also kind of love looking at the historical development of words, semantics, and spelling. This is why the Oxford English Dictionary, following the method of Dr. Johnson’s great achievement, is such an important historical resource, especially for scholars of Medieval and Early Modern literary culture, who are dealing with unfamiliar spellings in texts that preserve the integrity of the written word in its historical context. But actually I think we are in no danger of losing the history of words and their spellings and meanings. Not only do we have the OED, but we have an entire literary canon that shows us how words were used hundreds of years ago because editors care enough to preserve original spellings. We also have things like Early English Books Online where we can see very old texts and their incredible notations that are no longer used, but were deliberately employed at the time.

LikeLike

Chelcy,

This was an absolutely unique and insightful article that I loved listening to and rereading.

I admit that this was a topic I have been mulling around in my mind ever since I pursued a degree in English. Ever since I became an English major, I was constantly approached by friends on what particular spelling they should use: blond vs. blonde, analyze vs. analyse, and disc vs. disk amongst others. Just last week I was asked by a friend whether she should use “catalogue” or “catalog.” So the topic of your paper and article were very poignant for me because I was certainly wondering why “catalog” was still considered an equal spelling variant for “catalogue” when everyone I inquired about the subject said they spell it “catalogue.” Needless to say, I certainly found this article to be extremely relatable.

Early in the history of the English language, there were a great number of spelling variants for each word. That is certainly understandable, and the existence of variants today is still understandable if the spellings are American spellings vs. British spellings. However some variants are not widely used by either nationality and have become pretty much extinct because of the lack of use. I find it absurd that some sources still consider these outdated spellings equal to the spellings that are actually widely used. This is misinforming people that are learning English as a second language. Native English speakers almost instinctually know which spelling variant to use because it is the language that we grew up learning, however non-native speakers are disadvantaged in this respect. Now that we have the technology to make drastic changes, I believe we have an obligation to make note of these outdated variants and make it clear which variants are the accepted spellings. It would be foolish to get rid of these spellings completely because doing so would be trying to get rid of our language’s history, but we do need to make changes to these programs that weigh outdated spellings against the spelling that is actually widely used.

LikeLike

I actually think it’s quite hilarious that you chose to write about this topic. This is something that I’ve come across during my time studying, and it’s floated by without much thought other than “I wonder why this word is spelled like that.” The tone you used to attack this topic is also interesting and made your paper amusing to read—it’s very much appreciated. It seems exhausting to think about all the different spellings there are for one word.

However, I will say, even though I loved everything you had to say and how you went about the topic, I do disagree with an aspect of your opinion in the last paragraph. First, I do think that the English spelling is confusing enough and I do also agree that the masses have chosen certain spellings over others. However, I disagree with your idea of retiring the outdated spellings. I think that the outdated spellings create a sense of identity, culture, and tradition. For example somebody might prefer to use “Shakespearian” over “Shakespearean” because of the research and other work they’ve conducted in the literary and scholarly field. It also may create a sense of identity in their writing, or for them as a person. As silly as this may sound, we can’t just forgot where we came from, and how language has developed. It is a part of our history. Language defines who we are as human beings (all misspellings and multi-spellings included). I think that it would be helpful for these dictionaries you mentioned to better organize how they present the historical spellings and be more selective on how they re-route to different variants.

LikeLike

I am torn on this issue, because though I personally appreciate the complexity and history that the preservation of spelling variants provides, Linda’s comment helped me see that my perspective is informed by my privilege as a native English speaker. As she suggests, I think there is value in having an authoritative institution, like a major dictionary, make a decision on which variant is preferred so that people learning the language have something solid to reference. As Mark points out, we’ll always have the OED to show us the history of a word’s usage.

My opinion on this point would be different if we were discussing a less dominant world language—for example, an extremely localized indigenous language that people were fighting to preserve. I think the history and variant decisions in the case of a less documented language would need to be considered much more carefully. English, on the other hand, has been largely forced on people through colonization and current movements to “nationalize” it as the official language through which all legal and other necessary transactions must be conducted in the U.S. If we are going to judge people on their ability to conform to a standard, we have a responsibility to “spell out” what that standard actually is.

In general, I am really interested in the evolution of language over time, and how that process both reflects our society’s evolution and inhibits us from understanding the (untranslated) perspectives of those in the past. The example I always remember is the impossibility of labeling nuclear waste so that future generations will understand the dangers associated with it. (Some radioactive waste can be deadly for more than 500,000 years, while anatomically modern humans have only existed for about 200,000 years.) I don’t think language evolution is a process we can stop, but I do think it can be dangerous in some ways.

LikeLike

I love that you focused on the differences and the variations of words in the English language. I have always believed that the English language is incredibly strange and impossible to learn completely. Especially the subtle differences in the spelling of words can be very tricky; like the difference between grey and gray, canceled and cancelled. Who came up with either of these? When typed into Word neither of them show the red squiggle of shame. Though at this point we know not to trust Word’s spell check completely… I especially liked your point about preference. It is fascinating that the language that we use today is only thought to be appropriate and correct because a number of people approved all of the different aspects of it. The same ideology of preference appears when we talk about editing and what the ‘house style’ is. I wonder if there would be a way for you to create a Google Ngram for a certain publishing houses ‘house style’ to see where they compare to another publishing house in the same field. I think that seeing the difference between the spellings of words that different companies use would be really interesting to see. Like in your example, if two different publishers use Shakespearian and Shakesperean, and the reasons behind their decisions. It’s all about preference and I think you found a great aspect of the English language to focus on.

LikeLike

Chelsey, I thought all the questions you posed in regards to who should shoulder the responsibility of the somewhat confusing lists of variants in the American language, interesting. I’m not sure if it is a burden for an editor though, to create their own personal style guide from all the contradictory sources available. I am sure it is no easy task, but perhaps since the editor is personally in charge of the selection for their guide (our professor and the VPR Guide as an ex.), rules that may personally seem more clear and make the most sense to you, is easier, or at least ultimately less work than others. Having a personal style guide removes the repetitive process of looking through multiple sources, primarily with a collegiate dictionary and picking through it constantly. How do you decide which variants to use is difficult until you make that initial decision, then the rule is to simply stay consistent. But, it is really quite confusing as to why they exist in the first place and why variants are simultaneously allowed by certain sources and denied by others. I suppose this is just another editorial decision we have to face.

LikeLike