SELENA EFTHIMIOU

We are not interested in those stupid crimes that you have committed. The Party is not interested in the overt act: the thought is all we care about. We do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them. Do you understand that?[1]

-George Orwell, 1984

We are being watched and tracked and Big Brother—the companies, corporation, and capitalistic power—is keeping tabs. Yet, in the land of the free our privacy is being invaded. So yes, Orwell, in the digital age of e-books and publishing, I do understand. I hear you loud and clear.

So often we turn to our devices to escape, especially when wanting to avoid awkward situations with people. I’ve observed the unlocking of an iPhone to avoid a conversation and shamefully, I too, have been at fault for this. Yet, people do this to avoid the world around them and enter a more private one—the Internet and all its glorious treasures. This online sphere allows for a private experience for only you and your eyes. Yet, even though only our eyes are transfixed on our private screens, other eyes are hidden within watching our every move. Carpenter’s article, “Trust, Privacy, Big Data, and e-Book Readers” questions the eyes watching over and tracking our activity in the “private” world of the Internet. More specifically he further examines the tracking of downloaded e-books. In the article he makes the claim that digital updates “address the security flaw of transmitting these data in the clear, ‘allowing anyone who can monitor network traffic (such as the National Security Agency, Internet service providers and cable companies, or others sharing a public Wi-Fi network) to follow along over readers’ shoulder.'”[2] Which leads me to question, is it possible to escape into an e-book without being tracked or monitored? If our thoughts are only what corporations care about in order to advertise and market accordingly, how can we truly make our thoughts and actions private while reading e-books? Is this even possible?

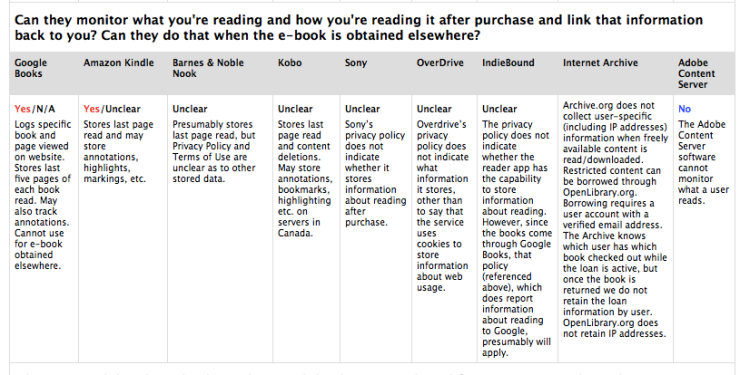

You would think the easy answer to the question would be, “ok then just go to the library and check out a book. You will avoid all advertisements, distractions, and promotional emails barricading your way into the literary world.” Although I, personally, would much rather read from a printed text, e-books are not going away and this invasion of privacy has presented a problem that readers are claiming must be solved. In addition, Carpenter later states readers don’t necessarily know why we are being tracked and what the information is used for. However, in the 2012 article “Who’s Tracking Your Reading Habits? An E-book Buyer’s Guide to Privacy, 2012 Edition,” Cindy Cohn and Parker Higgins answer these exact questions. In their research they asked seven different questions regarding e-book tracking at Google Books, Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Nobel Nook, Kobo, Sony, OverDrive, IndieBound, Internet Archive, and Adobe Content Server.[3] Most importantly they discovered whether or not these companies could monitor what people are reading and how they are reading books after purchase. They also examined whether or not that information could be linked back to you. In addition, could this linkage be conducted if the e-book is obtained elsewhere? Taking a closer look at their charts, both Google Books and Amazon Kindle claimed they do monitor what people are reading and how they are reading books after purchase. Google claims their company “log[s] specific book[s] and page[s] viewed on website. Stores last five pages of each book read. May also track annotations.”[4] Similarly, Amazon Kindle was the only company that also claimed they did this, stating the company “stores last page read and may store annotations, highlights, markings, etc.”[5] With the exception of Adobe Content Server who denied any monitoring of how books are read, all the other companies were unclear in their answers to this question (See Table 1).

As a reader, I had no idea this was happening. In fact, I had no idea it was possible to store a reader’s annotations and ideas. The misconception is seen when purchasing a book. So often, true book lovers will purchase a text with the intent of filling it with their ideas, questions, comments, explorations, and experiences. When these thoughts are inscribed upon the pages, the book transforms. It becomes a storehouse of the reader’s emotions and experiences at that moment. To emphasize, this becomes a private dialogue with the book. When an e-book is purchased, these readers intend to read the book in the same way because that is what they’re used to.

As indicated from the highlighted areas above, all of the companies use vague language except Adobe Content Server. It isn’t reassuring to know that Google Books, Amazon Kindle, and Kobo use the word “may” to indicate whether or not they are able to track annotations, highlights, markings etc. In all honesty, “may” doesn’t answer the question, leaving the reader to become skeptical. In addition, Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, Kobo, Sony, OverDrive, and Indiebound are all “unclear” on whether or not they are able to save annotations and other types of usage from the e-book purchased. In fact, to add to the this uncertainty, IndieBound specifies that they simply do as Google does: “Since the books come through Google Books, which does report information about reading to Google, presumably [the same] will apply.”[6]

In addition, because this article was written in 2012, I looked into how much has changed since then. Taking a closer look into 2014 (last updated) “Terms of Use” for Amazon’s Kindle, I discovered that although the page was difficult to find it was easier to understand than a few years ago. Under the headings “General” and “Information Received” Amazon notes, “The Software will provide Amazon with information about use of your Kindle or Reading Application and its interaction with Digital Content and the Service (such as last page read, content archiving, available memory, up-time, log files, voice information, and signal strength). Information provided to Amazon may be stored on servers outside the country in which you live. We will handle any information we receive in accordance with the Amazon.com Privacy Notice.”[7] In this 2014 update, they seem to have omitted the uncertainties of what they store, and added uncertainties to where they store the information. Amongst the uncertainties and the vague “may/may not” language, I catch myself questioning why? Why the vague language? What purpose does it serve? For whom does the nebulous language benefit?

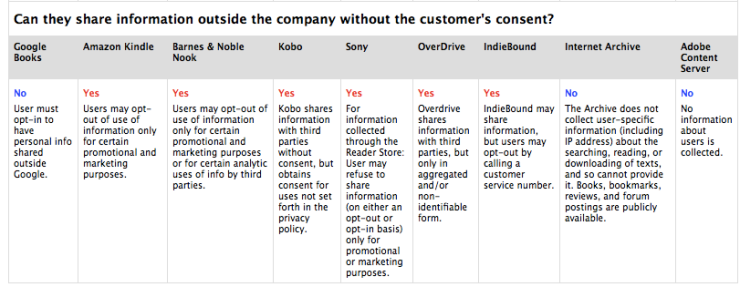

The last information I found quite interesting and suspicious was that all but Google Books, Internet Archive, and Adobe Content Server can share information outside the company without the customer’s consent. More specifically, Table 2 outlines with whom our information can be shared.

If you notice, only Google Books, Internet Archive, and Adobe Content Server claim they do not share information outside the company. However, when taking a closer look at the language used, Google claims that a “user must opt-in to have personal info shared outside Google.”[8] In other words, the reader must have to dig through settings, privacy policies and jargon to figure out how to opt-in to having their information shared. Although this may seem like a good approach for protecting information, the same method is used for Amazon Kindle, Barnes and Noble Nook Kobo, Sony, and IndieBound, but to opt-out of having information stored. Consequently, the consumer must dig through the same sort of privacy policy and settings simply to withdraw our information from being used outside the company.

Which leads me to my next point of realization. How often do I find myself trying to purchase something online and have to accept the “Terms of Agreement?” Quit often. How often do I read the “Terms of Agreement” with a careful eye, specifically looking for how my information will be used? Never. In fact, I never read them. I simply scroll to the bottom of the window and blindly click “Accept.” It seems as if the ways of consent are constructed to benefit the company rather than the consumer. Again, I catch myself asking why? Why do companies construct their methods for consumer consent in misleading and deceiving ways? What purpose does it serve?

What frustrates me the most is that so many of us are putting our trust into the Internet and more specifically these companies we buy from. We automatically assume that they will apply the same privacy policy online as they would in stores or in libraries. Yet I’m realizing that is a very naïve way of thinking. What I find equally disturbing and unsettling is that all of this tracking is happening without our knowing consent. Although Cohn and Higgins did investigate where the information gathered is going, we are still left in the dark in terms of why. Why do these companies assume this is morally right to invade on the privacy of readers? Why do they find it necessary to share and link information, especially without our consent? Furthermore, by spying on our annotations, highlights, and other markings (as Amazon Kindle apparently does) they are gaining inside information of our personal thoughts. In other words, they are gaining access into the magic that is created between a book and its reader. As readers we choose to read books for the private relationship. Readers become vulnerable within a text and allow themselves to escape into worlds created solely for them. How is it morally right for these companies to steal this away from us?

As I still try and wrap my mind around how companies are allowed to do this, I keep hearing Orwell’s voice: the thought is all we care about. We do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them. Now maybe I’m thinking too deeply into this and maybe I’m entering a state of paranoia, but I can’t get passed the idea that quite possibly our reading habits and ideas will change because of greater use with digital e-books. Knowing that there are eyes on the other side with access to our thoughts, is it valid to think that fewer and fewer people will annotate? If it is, then fewer ideas will be explored, and less experiences and emotions evoked through reading will be remembered. Ultimately, the reader’s ideas will not be made real through the use of writing and “jotting down.” As a result of this undoing, ideas will become fleeting moments and vanish.

NOTES

- Orwell, 1984, 253.

- Carpenter, “Trust, Privacy, Big Data, and e-Book Readers.”

- Cohn and Higgins, “Who’s Tracking Your Reading Habits? An E-book Buyer’s Guide to Privacy, 2012 Edition.” The following seven questions are examined in article: “Can they keep track of searches for books? Can they monitor what you’re reading and how you’re reading it after purchase and link that information back to you? Can they do that when the e-book is obtained elsewhere? What compatibility does the device have with books not purchased from an associated eBook store? Do they keep a record of book purchases? Can they track book purchases or acquisitions made from other sources? With whom can they share the information collected in non-aggregated form? Do they have mechanisms for customers to access, correct, or delete the information? Can they share information outside the company without the customer’s consent?”

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Amazon; Help and Customer Service; “Kindle Terms of Use.”

- Cohn and Higgins, “Who’s Tracking Your Reading Habits? An E-book Buyer’s Guide to Privacy, 2012 Edition.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Amazon; Help & Customer Service; “Kindle Terms of Use,” accessed April 22, 2015, http://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=200506200.

Carpenter, Todd. “Trust, Privacy, Big Data, and e-Book Readers.” The Scholarly Kitchen. Last modified October 9, 2014. http://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2014/10/09/trust-privacy-big-data-and-e-book-readers.

Cohn, Cindy and Higgins, Parker. “Who’s Tracking Your Reading Habits? An E-book Buyer’s Guide to Privacy, 2012 Edition.” Electronic Frontier Foundation. Last modified November 29, 2012. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2012/11/e-reader-privacy-chart-2012-update.

Orwell, George, 1984. New York: Signet Classics. 1977.

Selena,

Your posting brought up new privacy concerns that I had never thought of before. It seems there are endless possibilities to the desire for personal information and data about people and their habits. Something as innocent as a highlighted word in an electronic text, can be used for the financial gain of a company. Scary.

I think your quote about Amazon’s collecting of voice information and signal strength is the creepiest idea of all. It has been reported in the media that small microphones in devices have been used for sinister purposes, phone records are often collected, and location data is used for marketing purposes. This really does seem to be Orwellian.

As you point out, the only options are to opt-out of privacy policy agreements or scroll through and tick the box. Simply, a consumer can allow access to personal information, or not use the tools. This can create a complicated power struggle. For instance, if a student is required to use an electronic version for a class, they have no choice but to agree. Giving these companies (such as Amazon) access to personal data may not be preferred, but with some applications, required. Thankfully, a quick internet search pointed out that there are groups such as the Electronic Privacy Information Center currently working on these issues. Hopefully these watchdog agencies will be on guard, and help to pass legislation making tracking less of an option and protect us from a modern day “big brother.”

LikeLike

Selena,

Great points! This is scary, especially when considering that much of this tracking likely masks economic/marketing strategies for big companies. Never before have businesses had such an easily accessible insider’s perspective on our reading desires and habits.

However, based off of some of our reading last week, I wonder if it is true that “Readers become vulnerable within a text and allow themselves to escape into worlds created solely for them.” Were these worlds created “solely” for us as individuals? Or is there a type of community to writing, publishing, and reading–a community that maybe is hidden in our modern-day print culture?

Further, I wonder if we don’t have something to gain from this, as well. Because the data is likely being used to market more specifically to us as individuals, I wonder if we don’t actually benefit from the personalized marketing. It’s as though you’re in a Buckle store with a sales associate all to yourself; you tell them kind of what you want, and they help you find the perfect fit. I wonder if that happens, too, with our books. For instance, when I look up Said’s Orientalism, Amazon pulls up Culture and Imperialism, Imagined Communities, Black Skin, White Masks, and a host of other related books. I, I think, benefit from this, so is there a way we can consider this tracking as mutually beneficial for both business and consumer?

Either way, though, it’s definitely a creepy process, and I think we have a right as individuals to question the reality of our privacy. Maybe we could negotiate to some type of opt-in tracking in which Google, Amazon, etc., would have you check a box (that’s not mandatory) that allows them to track what you read? In that, I think the businesses would be forced to expand on the ways in which this tracking is mutually beneficial.

LikeLike

My guess is that most of these companies are, in fact, storing this type of information for the purposes of marketing, analytics, and promotion. This is how they are able to track what is popularly sold and what they can recommend for further purchasing and customer retention. This all seems rather harmless to me–I rarely look at what is recommended and the range of my online purchases are so small that these tracking tools are not all that helpful when looking at my activity. But I think you’re absolutely right to be suspicious of this whole process, and especially of the ways companies are guarding their purposes, assuring the public through vague language that it’s just to help their marketing programs. And it probably is for those purposes at the moment, but the reason they safeguard information about this is because companies are certainly developing other ways of using the information they collect, and the frightening thing is that the possibilities are endless.

LikeLike

One of the most fascinating aspects of this post to me is the first chart that you included, Selena. The chart notes that Google Books, Amazon Kindle, and Kobo all store reader information such as highlighting, annotations, bookmarks, markings, etc. My question is, who reads these? My guess would be that these kinds of markings (annotations especially) are not able to be scanned or “read” by a computer or data analysis program. So my assumption would be that a live person is responsible for going through these markings in order to determine their use in aiding marketing strategies for these companies, which in turn makes me wonder how this type of data is able to be quantified? How can one person read another person’s comment of “interesting” or “good point” next to a sentence in book and then based on that simple reader activity, calculate how to market other products to them? There must be some type of formula or guidelines that these companies follow, but it mystifies me as to what they could be.

In the end I wonder how effective this practice of sifting through reader annotations is, and if its even worth the company’s time and resources. By Mark’s admission above he doesn’t really look at the recommendations, and I admit that neither do I. I wonder if each of these companies suspended this type of tracking and focused on other resources for marketing, would they notice a drastic difference in sales? Or would they find that this type of information is hardly worth tracking, and perhaps leave readers to comment, highlight, and mark in peace.

LikeLike

I share the sentiments of others who are not overly alarmed at the thought of Amazon, Barnes & Noble, et al, tracking customers’ online activity, although I admit that I am mostly naïve about this subject. The Orwell quote is a great one, especially this part: “We do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them.” It makes me wonder how the companies you mention, Selena, might try to “change” their customers. Sure, there are the standard marketing techniques designed to influence consumer behavior, but could it go beyond that? I suppose Amazon could implement a policy of only recommending books that align with the company’s values (in the hope of influencing readers whose values are different), or Barnes & Noble could share with authors the notes that Nook readers make on their devices (so that those authors could modify future books to be more persuasive toward a particular agenda), but for all I know that is already happening–and it does not seem terribly nefarious.

If I did a lot of e-reading, which I do not, I would be more concerned that all of the comments I logged on the “pages” of my electronic device would not be accessible years down the road. One of the best things about revisiting my old books is that I can see what I underlined or commented on, especially if it is a book that I read for an undergraduate English course. Do Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and the rest make any promises about the long-term durability of their technology? I have not looked into that, but I am guessing the answer is no.

LikeLike

Selena,

What a fantastic post! I loved reading it again after hearing your presentation on the matter. I found the topic very applicable to my life since I do own a kindle. I got a kindle for the sake of convenience since I studied abroad last year. We were required to bring along the novels and textbooks overseas despite having a forty pound weight limit for our suitcases. Needless to say, having a kindle eliminated the anxiety about that weight limit since I didn’t need to bring the books with me. Until this point I have been so focused on the convenience aspect of the kindle that it did not even occur to me that they may be using my data for any purpose other than recommending books to me that I may like based upon my past purchases. Quite obviously, you have opened my eyes to this problem and made me much more aware than I was. I am certainly much more cautious now when approaching my kindle, which feels odd since I read for fun so approaching something I do for fun with caution. This revelation has strengthened my preference to physical copies even more than ebook versions of the text. My purchases of ebooks have dropped significantly within the past months because of this preference and my decision not to buy ebooks unless I cannot find the physical copies anywhere else.

One day I do hope these companies provide us with more information on what they are doing and intend to do with the data because I believe consumers of these products deserve to know that their data is not entirely their own. Maybe someday a law will be passed forcing them to share this information because, until that happens I highly doubt the companies will share this information on their own accord since they have not done so already.

Thank you so much for the informative post!

Sincerely,

Linda Wetherall

LikeLike

Selena,

Not gonna lie, I love 1984. It’s a fantastic novel for high school and a wonderful metaphor for your essay! It is actually an incredible issue that you found. I don’t have a Kindle machine thing but I do have the Kindle app for my iPad. I never knew before you brought it up that they actually save all of our information to share. I knew that they save all of my info because it always shows what I have already highlighted when I bring up the book I was reading again, even months later. But there is definitely a lack of user data privacy. Amazon obviously knows the users identity, what they’re reading, when they finish a book, what page they’re on, how long they spend on each page, and what they’ve highlighted. While I do feel a little uncomfortable as the reader of ebooks I also think that it is important to look at the issue from the side of the publisher. The ebook market is has exploded and is continuing to thrive and being able to save that information is the only way for publishers to know the readers progress and in that they will be able to interpret how engaged the readers are with their novels. Publishing houses definitely put their use of the information over a sense of invaded privacy. With all of this information that they are being provided with they can find out what books are selling, why they’re selling, where in the world, how fast people read them, and at what points in the book they read faster or slower. That information would be extremely interesting to see. Thinking of the pace of most novels it would be fascinating to see how quickly readers get through the beginning where the author is introducing characters and the climax when the action gets really good. I do feel a little invaded but in the end I think that it may help publishers determine what kinds of books that they want to publish.

LikeLike